3 Updates Worth Noting from the Latest Consensus Guidelines in Sports Related Concussion

After months of anticipation it is finally here. The Consensus statement on concussion in sport from the 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, held in Amsterdam in October 2022, was just published in the June 2023 edition of the British Journal of Sports Medicine. This document brings together the latest research and recommendations regarding sports related concussion.

For some of us who have been treating concussion for decades it has been interesting to observe the changes with each consensus statement as more and more research is being done in the field of sports related concussion. It has also been great to see these consensus statements bringing the health care community together so we are all talking the same talk and providing consistent recommendations between care providers.

Let's dive into the highlights and explore the three key updates you should know about:

Concussion definition

Before we do that let's review what a concussion is. The definition of a sports related concussion was tweaked slightly from the 2016 consensus guidelines. That being said it is interesting that the current definition was accepted as a majority agreement (78.6% agreement), but did not achieve the 80% agreement to achieve consensus.

Definition: Sport-related concussion is a traumatic brain injury caused by a direct blow to the head, neck or body resulting in an impulsive force being transmitted to the brain that occurs in sports and exercise-related activities. This initiates a neurotransmitter and metabolic cascade, with possible axonal injury, blood flow change and inflammation affecting the brain. Symptoms and signs may present immediately, or evolve over minutes or hours, and commonly resolve within days, but may be prolonged.

No abnormality is seen on standard structural neuroimaging studies (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging T1- and T2-weighted images), but in the research setting, abnormalities may be present on functional, blood flow or metabolic imaging studies.

Sport-related concussion results in a range of clinical symptoms and signs that may or may not involve loss of consciousness. The clinical symptoms and signs of concussion cannot be explained solely by (but may occur concomitantly with) drug, alcohol, or medication use, other injuries (such as cervical injuries, peripheral vestibular dysfunction) or other comorbidities (such as psychological factors or coexisting medical conditions).

Update #1: SCAT6 vs SCOAT6

Based on the research, the SCAT has optimum utility within the first 72 hours after a suspected sports related concussion. The SCOAT6 and Child SCOAT6 are new tools intended for multimodal and serial testing conducted in the office after the initial 72 hours. The SCAT6 and Child SCAT6 are the most recent version of the SCAT and should be used within the initial 72 hours.

Some of the changes from the SCAT5 to the SCAT6 include the following:

- Starting with a 10 word immediate recall instead of 5 words.

- Documentation of any neck tenderness on palpation.

- Documentation of abnormal extra-ocular eye motion.

- A timed tandem walk, with an optional cognitive component.

We recommend you reviewing the SCAT6 and Child SCAT6 to understand all of the testing parameters.

Update #2: Rest & Exercise

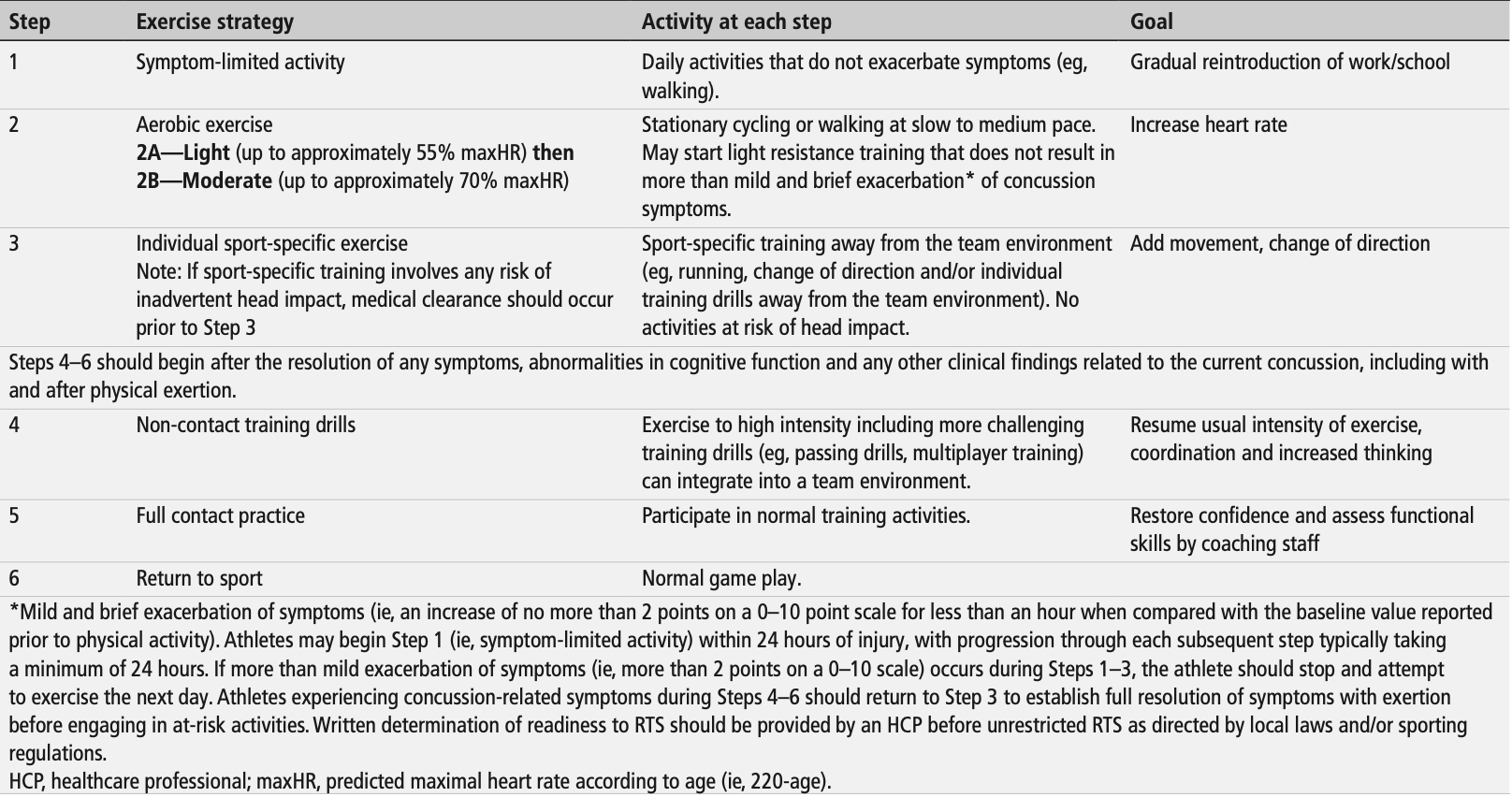

Unlike previous consensus statements the athlete can now progress activity, with symptoms, in the acute stage as long as the symptoms do not increase more than 2 on a 0-10 scale or the increased symptoms do no last for more than an hour. Gradual progression of aerobic exercise and regular daily activity is encouraged within 2-10 days after the concussion.

With progression of return to play there are also new specific cardiovascular parameters added for Step 2: initially up to 55% of maximum heart rate, then up to 70% of maximum heart rate (see below).

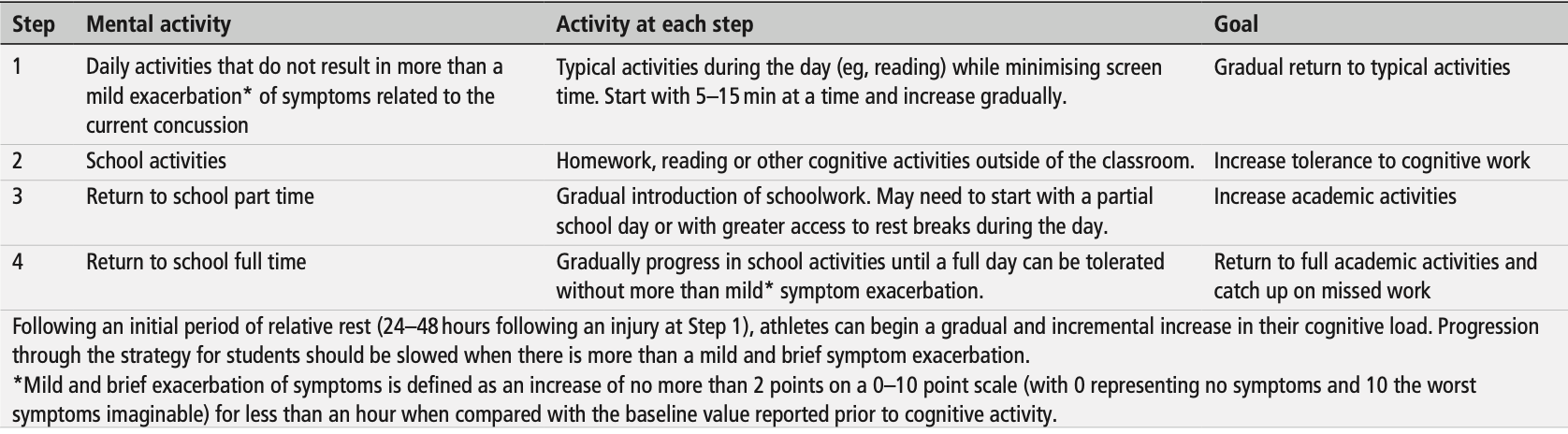

Additionally, this latest consensus statement provides useful parameters for return to learning, which were not included in previous consensus statements (see below).

Of note, the consensus statement indicated that with the systematic review 93% of injured athletes (all ages combined) returned to a full return to learn (with no additional support) within 10 days. To minimize academic and social disruptions they recommend avoiding complete rest and isolation, even for the initial 24–48 hours, and instead recommend a period of "relative rest".

Update #3: Referral

With this concussion statement there seemed to be more of an emphasis on referral. This is good as access to health care providers with specialized training in certain areas can reduce the occurrence of prolonged recoveries due to symptoms that may or may not be attributed to the concussion. This may include the management of cervicogenic symptoms, migraine and headache, cognitive and psychological difficulties, balance disturbances, vestibular signs and oculomotor manifestations.

What remains unchanged from the previous consensus statement

It's worth noting that some aspects remain unchanged from the previous consensus statement.

- The results of computerized neurocognitive tests should be interpreted in the context of broader clinical findings and are not to be used in isolation to inform management or diagnostic decisions.

- Advanced neuroimaging, biomarkers, genetic testing, and emerging technologies are still primarily used for research purposes.

- Treating persistent symptoms requires a multidisciplinary approach.

- The prognosis for functional recovery after a sports related concussion is positive.

A couple of other interesting notes in regards to concussion prevention

In terms of concussion prevention, the consensus statement highlights that mouthguards can reduce the concussion rate in ice hockey by 28% across all age groups. Furthermore, the policy of disallowing body checking in child and adolescent ice hockey has led to a 58% decrease in the rate of concussions during games.

Conclusions

While we've summarized some key points, we encourage you to read the full statement to explore more details that will help you based on your specific background and experience in this field.

The progress we're making in managing and preventing sports-related concussions is exciting, and we eagerly anticipate the next consensus statement in four years, which will undoubtedly bring more valuable insights.